- Ben Power

- Posts

- Are Aussies (and galahs) really reform ready? + Can Chalmers deliver? + The ‘productivity’ problem

Are Aussies (and galahs) really reform ready? + Can Chalmers deliver? + The ‘productivity’ problem

In a speech last year, Productivity Commission Chair, Danielle Wood, evoked Paul Keating’s famous ‘pet-shop galah’ line of 1989.

“If you walk into any pet shop in Australia, the resident galah will be talking about microeconomic policy,” the then Treasurer said.

Woods used the quote to make a point: at least back then people were talking about reform. Now, she laments, “it’s hard to get a human, let alone a bird, to have a casual chat about structural reform”.

With the Albanese Government’s Economic Reform Roundtable looming, people are beginning to talk about productivity and reform.

Commentator Paul Kelly has highlighted that previous reform eras were ‘elite driven’ – as is the current push.

But the people who truly grant or remove permission for the nation to move forward with reform are the Australian voters.

Advocates are going to have to better sell reform to the general public.

They need the average guy, girl and galah – not just the big end of town – to buy into productivity-enhancing changes to the Australian economy.

And that won’t be easy.

Difficult and complex

But reform has never been easy in Australia.

There is a lot of mythology around previous ‘Golden Ages’ of reform, particularly the 80s and 90s. But history shows us that far from being driven by a few swashbuckling politicians, reform was more complicated and difficult than many remember:

· For a start, it was a very slow process. As Treasury notes, compared with other countries, Australia’s economic reform took place over an extended period. It was the Whitlam Government, for example, that started dismantling tariffs with a shock 25% cut way back in 1973. But it then took decades for tariffs to be fully dismantled. Like now, the windfall of high commodity prices delayed the impetus to reform quickly like other countries.

· The push for reform usually followed a crisis, which advocates exploited to create urgency. The nasty recession of the 80s, as the RBA has pointed out, contributed to a sense of “national stagnation and decline” which galvanised debate.

· Past bouts of economic reform had support from multiple stakeholders: business, unions, politicians, academics, farming groups, and government agencies. These stakeholders included brilliant salespeople and communicators, particularly politicians, such as Paul Keating, Bob Hawke and John Howard. Both sides of Parliament supported reform. The Liberal Opposition harried Labor in the 80s and 90s for not moving fast enough.

· The reform sequence hasn’t always been smooth and optimal. Unlike other countries, the Australian economy was opened up before it was made fitter through internal microeconomic reforms.

· Reformers had to persist for years, even decades, and through major setbacks and the unintended consequences of prior reforms. Financial liberalisation in the 80s, for example, helped create the asset bubble that led to the severe recession of the early 1990s, a trauma that could have derailed reforms but for persistence.

But perhaps the biggest lesson is that reform only succeeded when it had broad public support. Reform was slow because advocates needed time to create “consensus building” and “get people on board”.

Australians are very cautious. Our top values, after all, are benevolence (welfare of family and friends) and security (personal and social safety and stability). Yes, we care about money, but we prefer safety.

Successful reform eras heavily focused on fairness and tried to ensure losers from some changes gained from other reforms. In that sense, Ross Gittins is right that broad-based reform is easier than one-off reforms because it disperses benefits and losses.

Australian voters only cautiously and slowly grant permission for policymakers to press ahead with reforms. The public rejected a GST in the 1980s and 1990s – including rejecting John Hewson at the 1993 election – before it was eventually implemented in 2000 after a long struggle.

And they can block reform (carbon emissions) or allow reforms to be unwound (industrial relations after WorkChoices) if they are unsupportive.

Creating awareness

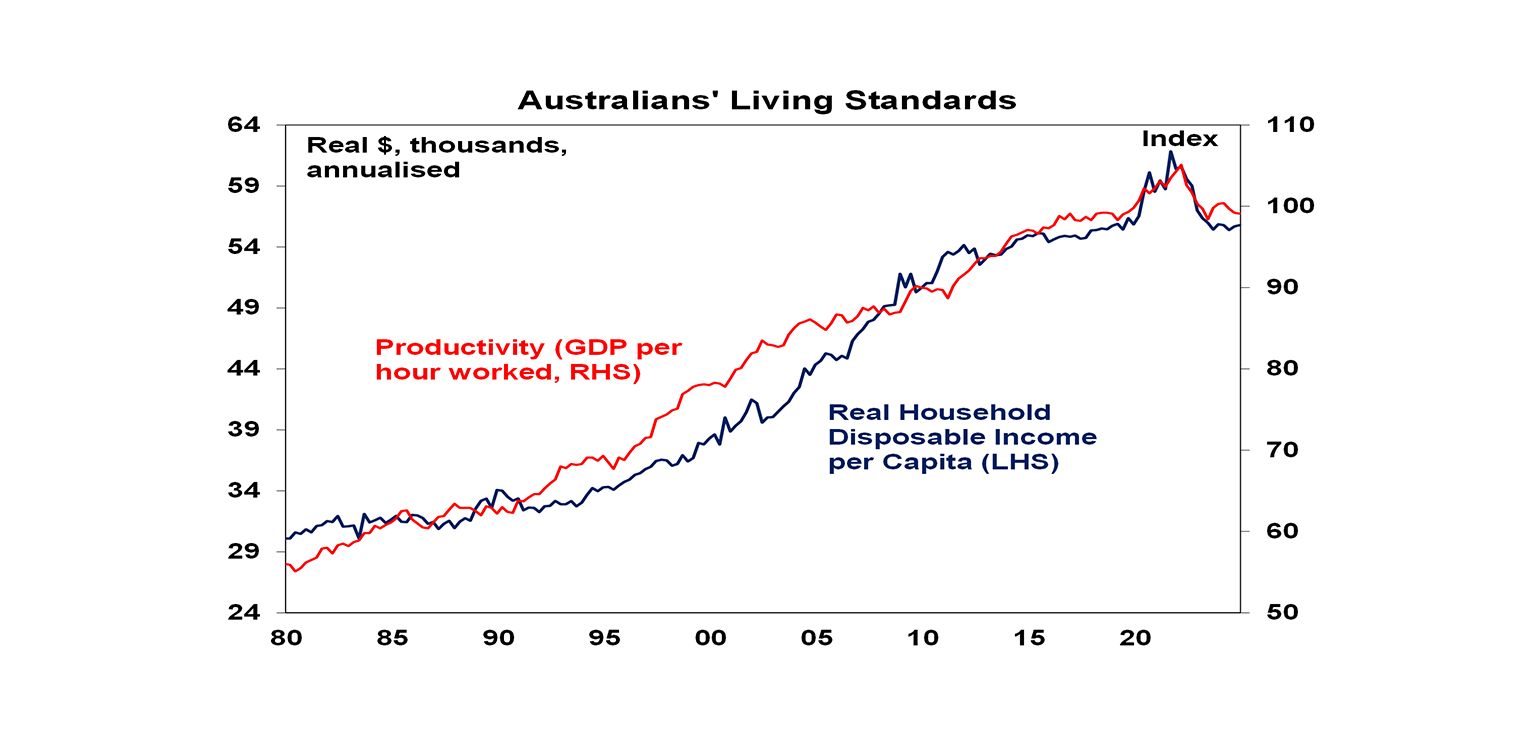

We do need reform now. The underlying Australian economy is performing poorly, with multiple per-capita GDP recessions, productivity at a 60-year low, slumping living standards and surging public debt.

Source: AMP

Yet the last election shows that Australians are not yet ready: They voted for an uninspired, business-as-usual government, and recent polling confirmed voters are lukewarm about bold changes.

In campaigning terms, we are only at the very start of any fresh reform round.

As campaign expert Chris Rose has highlighted, campaigns follow a typical pattern of evolving public emotions:

I’d suggest we are only now somewhere between awareness and concern.

Advocates – Paul Kelly’s elites who are driving the process again – therefore should be focused on raising concern and creating urgency among the broader Australian community.

The elites can’t only talk amongst themselves about ‘what’ reforms are necessary and ‘how’ they should be implemented.

They need to spend as much time convincing Australians ‘why’ they should buy into reform, how it will benefit them and how it will be done fairly.

The push for reform shouldn’t be only an ‘education’ campaign; it should also be a ‘motivation’ campaign to build that sense of urgency.

It needs to tell a story of decline and malaise; a story that has a happy ending if only we can get our economic act together.

Perhaps the best example of dramatizing reform was Paul Keating's warning in 1986 that Australia would become a third-rate economy, a ‘Banana Republic’, which helped shock Australians out of their complacency.

Economic reform in Australia is a slow, stop-start process that requires enormous persistence and brilliant communication, and it needs to bring the broader public along. Otherwise, it will fail.

***

Is Jim Chalmers the right man to deliver reform?

I worked closely with Jim at a strategic communications agency and I got to know him well.

While obviously not at Paul Keating’s level, he is an underrated economics communicator.

He hasn’t received enough credit for Albanese’s election romp. His selling of the pre-election budget was particularly masterful.

Many have questioned Jim’s commitment to economic reform, and I concur: he is primarily an uber politician and a Labor one.

His most disconcerting trait is a strong class warfare mindset.

Jim might recognise reform is needed, but he’s far from being a warrior. He won’t progress reform unless be can bring the average Australian along – he certainly won’t do anything rash that might spook voters.

To ardent reformers, this might be perceived as a weakness.

But, as we saw above, successful reform eras required a combination of persistence, caution, a focus on fairness, and great communication skills.

Jim definitely has the communication skills and empathy with the average voter to deliver reform in a way acceptable to Australians.

But his true test will be his real desire for change and his ability to persist in the face of inevitable opposition, as his predecessors did.

***

The problem with the word ‘productivity’ (and an alternative)

In a recent speech, the RBA’s Deputy Governor, Andrew Hauser, noted that reform Golden Ages were full of people who “specialised in translating big ideas into simple language”.

Productivity Commission’s Danielle Wood also argues that economists have an obligation to speak “directly and plainly” if they are to help drive reform.

Wood notes that an obstacle to clear communication is public servants’ and economists’ tendency to slip into “bureaucratese”, which she neatly describes as a “kind of passive word soup” that avoids committing to a point.

They also, she adds, “hide behind complex language and technical jargon”.

Passive language is one cause of the bureaucratese disease; but another, perhaps more insidious cause, is the dreaded ‘nominalisation’, something I spent a lot of my time unpacking when I ran Clear and Persuasive Business Communication workshops for major corporates.

Nominalisation is where you turn a verb or adjective into a noun. So the verb ‘decide’ becomes a noun ‘decision’.

Nominalisations are deadly to clear language because they lead to cold, abstract words; create passive, lengthy sentences; and often remove human actors … “we decided to move” … “the decision was made to move”.

And what is the big nominalisation of the moment?

That’s right: productivity.

We’ve turned the verb ‘produce’ into the noun ‘productivity’.

No wonder ‘productivity’ falls flat with the average punter.

Perhaps we could unwind the nominalisation by turning it back into an adjective.

Instead of talking about ‘productivity’, maybe we could talk about creating a ‘Productive Australia’.